A New Way of Thinking About Sexual Orientation

May 9, 2022 by Justin Lehmiller

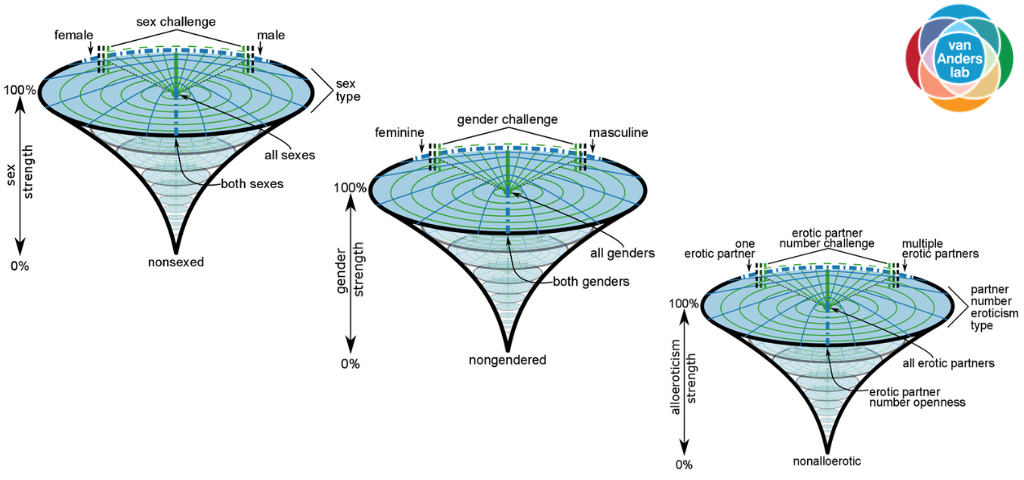

Sexual fantasy, pornography use, and in-person sexual behavior each tell us something unique about our sexuality, which means we can’t just assume that sexual interests in one context, transcend other contexts. This makes the study of sexual orientation complex. We need to take a multi-dimensional view to understand how all of our sexual interests come together. This is where Sexual Configurations Theory (SCT) comes into play.

I recently interviewed doctoral candidate Aki Gormezano and Dr. Sari van Anders, both from Queen’s University in Canada, for the Sex and Psychology Podcast. Aki is a PhD candidate in Social and Personality Psychology working with Sari, who is a professor of Psychology, Gender Studies, and Neuroscience.

Below is an excerpt from our conversation (you can listen to it in full in this podcast) in which we talk all about SCT and how it can help us to better understand and measure sexual diversity. Note that this transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Justin Lehmiller: Let’s start by talking about how you conceptualize sexual orientation. I recently did an episode of the show with Dr. Lisa Diamond and we talked a lot about sexual orientation and how researchers’ understanding of it has changed over time. Historically, it was primarily discussed in terms of patterns of sexual attraction based on sex or gender.

But, increasingly, scientists are looking at it as multi-dimensional. Lisa name-dropped you in that episode, Sari, and said that you were someone who was really influential in the way that she thinks about sexual orientation. She specifically mentioned Sexual Configurations Theory, which is something you developed.

Can you give us the brief version of how you define the concept of sexual orientation and this theory you developed? What does it try to do?

Sari van Anders: As you said, people used to think about sexual orientation as focusing only on sexual attractions. And sometimes, I kind of joke, it was like a genital matchup. Like what are your genitals relative to the genitals of those you’re attracted to. But of course, we know that many people’s attractions have nothing to do with genitals at all, or a genital matchup in any way. And one of the things I talk about with Sexual Configurations Theory, or SCT, is this sort of tripartite model of identity, orientation, and status. Identity being who you are, what your labels are, what your politics and communities are; orientation being your attractions or arousals and so on; and status being what you’re doing and with whom and in what ways.

And those can all be branched. So, we use the word ‘branched’ because people kind of assumed those all lined up or aligned. And actually, when you think about what the opposite of alignment is, as misalignment, people sort of thought of it as almost a problem when those don’t align. So, we use the language of branched (divergent) and coincident (overlapping), rather than alignment, nonalignment, or misalignment, to try to really get into our heads that identity, status, and orientation sometimes coincide and oftentimes don’t.

And even within orientations themselves, they can be about who you’re attracted to, what you’re aroused by, what you want, what you like. Those are not necessarily the same thing, either. Those can branch. So, for example, you can be aroused by the thought of engaging in threesomes, but you might only want to actually have sex with one other person and not multiple people. Those might be different kinds of things.

Sexual Configurations Theory gives us some language and some ways to think about that in relation to what we call gender/sex sexuality. The genders/sexes of people are an important part of attraction for many. Some people are attracted to men. Some people are attracted to people of any gender. Some people are attracted to people who are feminine regardless of their bodies or identities. Some people are attracted to certain kinds of bodies, regardless of who has them.

We also talk about partner-number sexuality, so whether you want to be sexual with anyone at all, or you don’t. Some people don’t, like many asexual people and others. We also talk about whether you want to be sexual with multiple people, or with just one other person. And this can also branch. For example, Demisexual people talk about attraction differences between nurturance and eroticism. Do you feel nurturantly connected to some people? Maybe you have nurturant interest in women, and you’re interested in being erotically sexual with men or people of any gender.

So, we’ve seen a lot of branchedness and coincidence in SCT that there’s no natural way for things to line up and that we’re just interested in how sexuality plays out in all those ways.

Justin Lehmiller: This brings in a whole bunch of different aspects of sexuality that people have historically talked about as being totally different, but it puts it all under this same umbrella. So, you can kind of locate where you are in the context of all of these broader interests. In this way, it brings in interest in polyamory and open relationships into the same space as your attractions based on sex/gender, and also other attractions and interests that you might have.

I like your theory a lot in the sense that it’s kind of this all-encompassing thing that can help us to kind of understand how all of these different aspects of our sexuality fit together.

Aki, in your new work, you focus on how different aspects of sexuality intersect, including porn use, fantasy, and in-person behavior. As you mentioned in your paper, many researchers have made the assumption that people’s sexual interests are the same across all of these contexts. And so they just study one or the other and they use these terms interchangeably to some degree.

Can you tell us a little bit about why you think it’s problematic to take that approach? Why is it problematic to just assume that what people look for in, say, porn necessarily reflects their fantasies and their real-life behaviors as well? What was the starting point or impetus for you wanting to look at how all of these things intersect and diverge?

Aki Gormezano: I don’t know if this is true for you, but I often find that starting with analogies related to food can be really helpful for explaining things related to sexuality. So, I’ll try one of those.

Justin Lehmiller: You can talk about food anytime.

Aki Gormezano: I think about it kind of like if you were to assume that the same things that people might want to eat for dinner, like hamburgers or steaks, is necessarily the same sort of thing that people are interested in eating right when they wake up for breakfast, when they might be more inclined to have something like cereal, Cheerios, bacon, or eggs. Just assuming that when somebody wakes up, rolls out of bed, and then wants a steak or a hamburger seems like a bit of a leap.

Studying what people are attracted to in-person can be somewhat difficult. A lot of researchers will use pornography as sexual stimuli in studies and use that to make inferences about what people are attracted to in-person. And sometimes this can make a lot of sense, except for the times in which it might not. My sense coming into this research was perhaps pornography is a different enough context or situation that people are interested in different things; same with sexual fantasy, where there’s just different constraints there and potentially different things that people are interested in.

So, we wanted to explore whether there is branching or branchedness between these different contexts, between fantasy, porn, and interest in sexuality. Because we see them as different enough situations where making this leap that interest in one automatically equates to interest in another might not always hold. It just seems like maybe going a step too far, or at least something that we should empirically investigate.

Justin Lehmiller: I love the food analogy that you used there, because I think that makes this really easy to understand. For example, when I look at food porn, I’m going to look at the cheese fries or nachos, or whatever. But then when I go out to an actual restaurant and order food, maybe I’ll get the salad instead.

Aki Gormezano: Oh, see, that’s even better. That’s even more on point.

Justin Lehmiller: So, you can be turned on by the cheese fries, but that doesn’t mean that’s actually what you’re going to put in your mouth later. Right? Because there’s all kinds of decisions that factor into what we do in real life versus what we might do in fantasy or in porn.

So when it comes to sex, what we fantasize about, what kind of porn we watch, and what we actually do with our partners could all potentially be quite different. And that’s why we need a broader theory of human sexuality to help us better understand when, why, and for whom our sexual interests diverge—and when they converge.

You can listen to our full conversation in this podcast.

Want to learn more about Sex and Psychology? Click here for more from the blog or here to listen to the podcast. Follow Sex and Psychology on Facebook, Twitter (@JustinLehmiller), or Reddit to receive updates. You can also follow Dr. Lehmiller on YouTube and Instagram.

Image Source: SCT diagrams, courtesy of Sari van Anders (2015)

Dr. Justin Lehmiller

Founder & Owner of Sex and PsychologyDr. Justin Lehmiller is a social psychologist and Research Fellow at The Kinsey Institute. He runs the Sex and Psychology blog and podcast and is author of the popular book Tell Me What You Want. Dr. Lehmiller is an award-winning educator, and a prolific researcher who has published more than 50 academic works.

Read full bio >