A Concise Guide to Reviewing Journal Articles in Psychology

March 14, 2012 by Justin Lehmiller

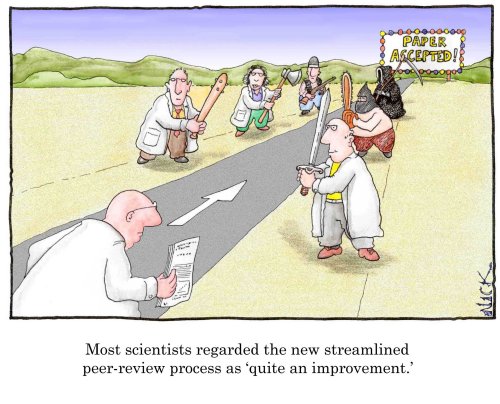

Any reputable scientific journal utilizes a peer-review process, in which each manuscript received is sent to a small group of experts to evaluate the work and determine whether it merits publication. This process is vital to maintaining the highest possible scientific standards, because (ideally) it serves to identify and weed out flawed research, correct errors and inaccuracies, and ensure clarity. Although this process is certainly far from perfect and every scientist who has gone through it has their gripes, it’s the best system we have for ensuring that only good quality research makes it into our journals.

Unfortunately, very few scientists receive formal training in how to conduct a proper article review. As a result, many reviewers end up focusing on the wrong things, which yields comments that are unhelpful and not constructive in the eyes of editors and authors. Moreover, it is common for reviewers to write much more than is necessary, which wastes time for everyone involved in the process. Because I have seen these and other problems arise again and again in my publishing experience, I have decided to share my philosophy on how to write a helpful and constructive article review with the hope that others will find it useful as a teaching and learning tool. While the steps below apply primarily to reviews of journal articles in the field of psychology, many of these points would likely be applicable in other disciplines.

Recommended Guidelines

Before you agree to review a manuscript, ask yourself whether the content area truly falls within your area of expertise and whether you have the ability to complete the review in a timely fashion. If you cannot confidently answer “yes” to both of these questions, you should probably decline the opportunity. However, please keep in mind that if you are publishing in journals, you also need to be reviewing and you must make time for this task. Each paper you submit makes work for an editor and several reviewers–so every time you submit a paper, plan on doing some reviewing in return, even if your paper gets rejected.

If you agree to conduct a review, your work begins with a very careful reading of the manuscript. As you do this, keep your eye trained on the big picture. Always remember that you are looking to evaluate the quality of the research—your job is not to evaluate the quality of the writing. Below is a non-exhaustive list of sample questions worth contemplating as you read the manuscript:

1. Is the literature review complete and accurately reported?

2. Are the theory and hypotheses clear and appropriate?

3. How sound were the research methods? Were the samples, experimental manipulations, and measures of high quality?

4. Were the statistical analyses appropriate and correct? Is any statistical information missing?

5. Are there any alternative explanations for the findings? Did the authors adequately acknowledge the limitations of their work and draw appropriate conclusions?

6. Does the research make a valuable contribution to the literature overall?

Take notes on the above questions while you read. However, please do not take notes on typographical or grammatical errors, sentence structure, and writing style. This is not part of the reviewer’s job! If the manuscript is ultimately accepted for publication, these issues will be corrected during the copyediting process. You are by no means the last gatekeeper prior to publication, so don’t worry about pointing out errors in the writing unless the author is making statements that are factually untrue or misleading. Also, while you may have certain stylistic preferences, keep in mind this is not your paper. It is someone else’s writing and, as such, should reflect their voice (even if it’s not as pretty as yours).

Once you are satisfied that you have identified any potential areas of concern (which may require a second reading of the paper), you can begin writing your review. There are no hard-and-fast rules for how your review should be structured, but I have found that the following formula works well:

Start with a brief recap of the work. I recommend just a sentence or two summarizing the paper’s approach and major finding(s) as a means of showing that you read and understood it. After this, describe the positive features of the research (e.g., the novelty of the research methods/questions, diversity of the sample, etc.). Highlighting the positives is just as important as documenting your critiques. All too often, reviewers seem bent on tearing the paper to shreds and, at most, they provide only token positive comments about how “interesting” the research question was. Try to avoid this because editors need to weigh the value of the work against the critiques. If I may sneak in a bit of social psychology, work on overcoming the negativity bias! After discussing the positive aspects, provide a concise overview of your major concerns and reservations about the work.

After writing your introductory comments, the remainder of your review should highlight point-by-point what you perceive as the major issues that either (1) make the paper unsuitable for publication in this journal or (2) that need to be addressed in order to make it publishable. If the paper is not publishable due to a fatal flaw (e.g., a confounding variable makes it impossible to know what was driving the effect), your review should be very short and focused primarily on that issue. There is no need to go on and on about other problems if something fundamental cannot be fixed. Don’t be one of those nasty reviewers who writes three page critiques of papers that could never be published under any circumstances just because they can. Your time is valuable, and picking apart an easy target is not a good use of it.

If you believe the paper is potentially publishable, you need to lay out each of your concerns and provide an example of how they could be addressed. If you feel strongly that an issue should be tackled in a certain way, don’t leave ambiguity in your comments. As you describe your concerns, try to lump them into groups so that common issues are addressed together (e.g., literature review omissions, statistical concerns, etc.). Again, restrict your comments only to the merits of the research, not the writing. My only caveat to this is that if the manuscript was so poorly written as to impede clarity or if things were reported inaccurately, then by all means, you should mention those kinds of writing problems because those are indeed major issues.

Most of my reviews address approximately five to seven areas of concern and all of my comments are easily contained on just one single-spaced page or less. I try to keep them shorter than that where possible, and it usually is. I think the ideal review is closer to one-half or three-quarters of a page. Keep in mind that you only need to say as much as is necessary to get your point across. Do not try to demonstrate just how smart you are by submitting a full-length manuscript of your own in return.

When you write your review, it is important to be extremely careful with your use of language at all times. Make sure that you write in a way that is professional and polite. Believe it or not, I have actually had more than one reviewer refer to my work as “silly” and my writing as “vacuous.” Language like that is not appropriate in a review. Do not belittle or berate the author(s) under any circumstances, even if they were critical of your work! The review process is not the time or place to wage personal attacks on your academic arch-nemeses.

How long should it take you to write a solid review? There is no simple answer to that because

it depends upon the length of the paper and the quality of the work. In my experience, the absolute best case scenario would be 60-90 minutes. However, if the paper is long, dense, and contains multiple studies, it can take quite a bit longer. It is for this reason that you should only accept review requests when you have the time to do them justice. I’ve received far too many reviews of my own work where it was clear that the reviewer rushed through the paper and misread or misinterpreted the findings. This is incredibly frustrating for authors and editors because it may completely invalidate a review and waste everyone’s time.

Conclusions

Reviewing articles is one of the most important and valuable services you can provide to the scientific community. However, writing a good review is challenging and can be quite time consuming. What I have tried to do here is share my views on what makes for an effective review and how to best use your time when you take part in the editorial process. I fully recognize that other scientists may have different views and philosophies on this, and I do not mean to imply that what I have described here is the only “correct” way to write a review. If you have other thoughts, please discuss and share! This is something that we desperately need to talk about as a field and find a way of better incorporating into our graduate training programs.

Want to learn more about Sex and Psychology ? Click here for previous articles or follow the blog on Facebook (facebook.com/psychologyofsex), Twitter (@JustinLehmiller), or Reddit (reddit.com/r/psychologyofsex) to receive updates. You can also follow Dr. Lehmiller on YouTube and Instagram.

Image Source: Nick D. Kim (Strange Matter)

Dr. Justin Lehmiller

Founder & Owner of Sex and PsychologyDr. Justin Lehmiller is a social psychologist and Research Fellow at The Kinsey Institute. He runs the Sex and Psychology blog and podcast and is author of the popular book Tell Me What You Want. Dr. Lehmiller is an award-winning educator, and a prolific researcher who has published more than 50 academic works.

Read full bio >