Unwanted Sex and Nonconsensual Sex are Not the Same Thing

June 15, 2020 by Justin Lehmiller

In recent years, I have noticed an increasing trend in both public and academic discourse on sex to conflate unwanted sexual activity with nonconsensual sexual activity. For example, in many studies of sexual victimization, “unwanted sexual contact” is often lumped into the same category as rape and other forms of sexual abuse [1].

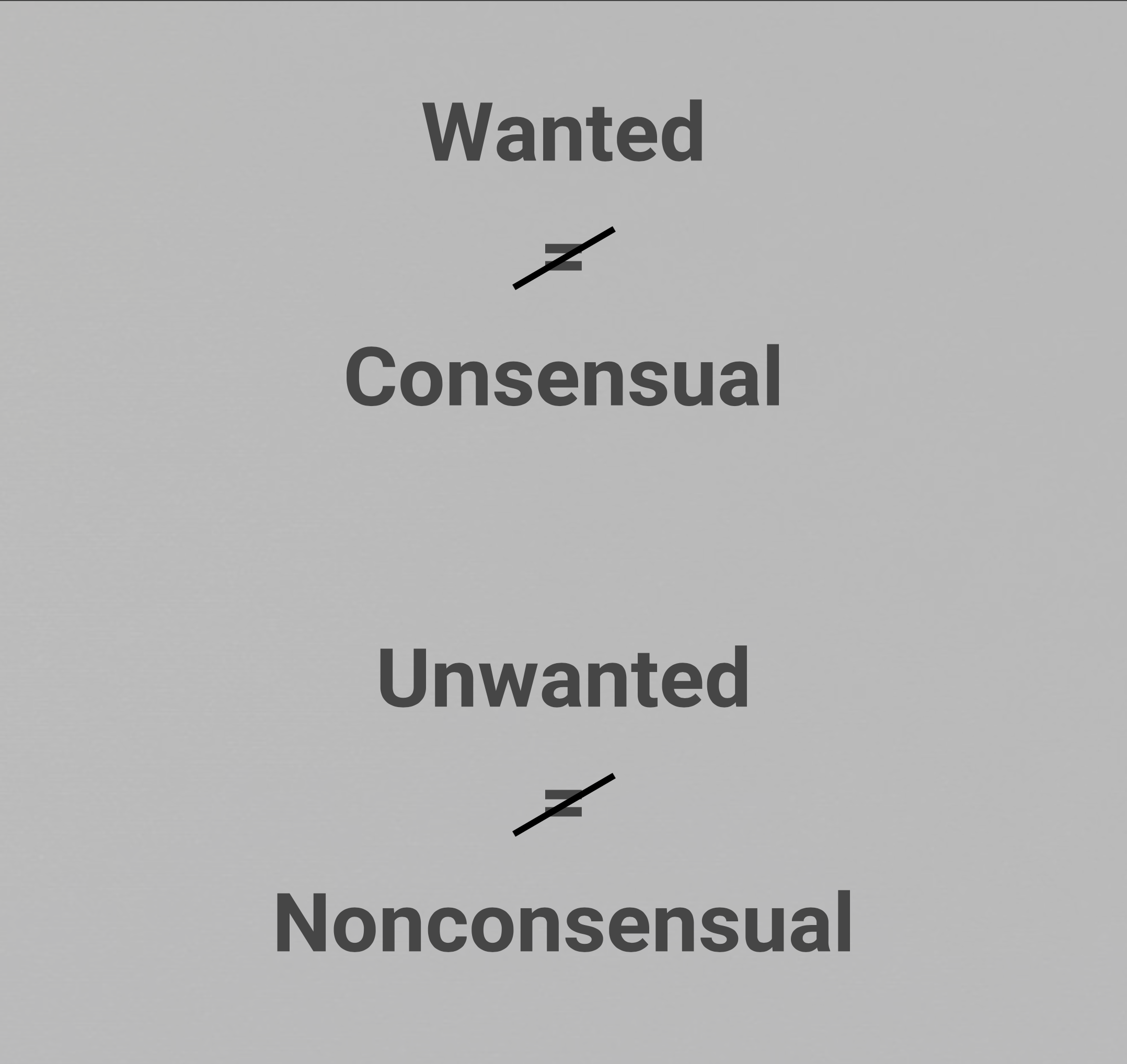

While it might make intuitive sense to assume that all wanted sex is consensual and all unwanted sex is nonconsensual, there is actually an important distinction to be made between wanting to have sex and consenting to sex.

In a 2007 study published in The Journal of Sex Research, researchers surveyed 339 college-age women [2]. Participants were asked to describe a previous sexual experience and to answer questions about both consent and wanting in that situation.

They found that consenting to sex and wanting sex were closely linked, such that consensual sex was generally reported as wanted and nonconsensual sex was generally reported as unwanted; however, they also found that “individuals sometimes consent to unwanted sex and sometimes do not consent to wanted sex.”

In fact, about 1 in 20 women who described a consensual sexual experience reported it as having been unwanted, while a similar number of women who described a nonconsensual experience reported it as wanted.

Why would someone consent to sex that is unwanted? There are several possible reasons. For example, one participant in this study described sex that she consented to and enjoyed but nonetheless classified as unwanted because she didn’t want to have sex outside of marriage. While she agreed to do it, it wasn’t what she wanted and she feels guilty about it.

As another example of how someone might consent to sex that they don’t want, consider asexual persons—persons who do not desire partnered sexual activity. Research has found that, despite not wanting to have sex, many asexual persons report having had sex before and some report willingness to do it again in the future [3].

Why do some asexual persons consent to sex they do not want? It’s important to recognize that being asexual does not necessarily mean that one is aromantic—many asexuals persons still want romantic relationships, and sometimes they partner with someone who is sexual. In these cases, some asexuals report a willingness to have sex because they want to please their partner.

Of course, sexual persons sometimes consent to sex that they don’t want for the very same reason: they might not be in the mood, but agree to have sex anyway because they want to make their partner happy. Research has found that this can even be beneficial for relationships—couples who are motivated to meet each other’s sexual needs (even when a partner’s needs might be different from one’s own) tend to be more satisfied with and committed to their relationships [4]. One caveat: this has to be reciprocal—in other words, it has to go both ways. If one partner is always sacrificing and striving to make the other happy but isn’t getting similar treatment in return, those relationships don’t tend to work out too well.

As yet one additional example of someone consenting to sex that they don’t want, think about sex workers. Sex workers consent to engaging in sexual activity for money, and the sex that they have often is not wanted or desired. For example, a sex worker may agree to have sex with someone to whom they are not attracted simply because it is part of their job.

Now, you might be wondering about the flip-side of this—how can someone say that a nonconsensual sexual experience was wanted? In a study where researchers asked people to describe experiences with nonconsensual sex, some described having wanted that sex for a range of reasons, such as feeling sexually aroused or because they thought it might enhance their image [5].

In other words, there was a certain level of want and desire for sex in these situations, but just because they wanted it doesn’t mean that they consented to it under the specific circumstances under which it took place. Think about it this way: people can want things—both sexual and non-sexual—but decide not to do them for a range of reasons (just like you might want to go out and party with friends tonight, but you don’t agree to go out with them because you need to work in the morning).

Making a distinction between wanting sex and consenting to sex has several important implications. For one thing, it has implications for researchers who study sexual victimization. If all unwanted sexual activity is automatically categorized as sexual assault, it means that some consensual experiences are going to wind up in this category, such as when people consent to unwanted sex with the goal of making their partner happy.

It also has implications for how we think about sexual assault more broadly. It’s common for people to dismiss rape and sexual assault allegations any time there is evidence that the person wanted sex. In these cases, victims are then—unfairly—blamed for their own assault because they “asked for it.” However, just because someone wants or desires sex doesn’t mean that they are providing blanket consent for anything that happens.

What all of this tells us is that, while wanting sex and consenting to sex usually go together, these concepts are not one and the same—and we would do well to recognize the distinction between them.

Want to learn more about Sex and Psychology ? Click here for previous articles or follow the blog on Facebook (facebook.com/psychologyofsex), Twitter (@JustinLehmiller), or Reddit (reddit.com/r/psychologyofsex) to receive updates. You can also follow Dr. Lehmiller on YouTube and Instagram.

[1] Fedina, L., Holmes, J. L., & Backes, B. L. (2018). Campus sexual assault: A systematic review of prevalence research from 2000 to 2015. Trauma, violence, & abuse, 19(1), 76-93.

[2] Peterson, Z. D., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (2007). Conceptualizing the “wantedness” of women’s consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences: Implications for how women label their experiences with rape. Journal of sex research, 44(1), 72-88.

[3] Hille, J. J., Simmons, M. K., & Sanders, S. A. (2019). “Sex” and the Ace Spectrum: Definitions of Sex, Behavioral Histories, and Future Interest for Individuals Who Identify as Asexual, Graysexual, or Demisexual. The Journal of Sex Research, 1-11.

[4] Muise, A., & Impett, E. A. (2015). Good, giving, and game: The relationship benefits of communal sexual motivation. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(2), 164-172.

[5] Satterfield, A. T., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (1996, November). The role of gender in the meaning of sexual coercion: Women’s and men’s reactions to their own experiences. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for the Scientific St

udy of Sexuality, Houston, TX. (As cited in Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2007)

You Might Also Like:

Dr. Justin Lehmiller

Founder & Owner of Sex and PsychologyDr. Justin Lehmiller is a social psychologist and Research Fellow at The Kinsey Institute. He runs the Sex and Psychology blog and podcast and is author of the popular book Tell Me What You Want. Dr. Lehmiller is an award-winning educator, and a prolific researcher who has published more than 50 academic works.

Read full bio >